Alcohol Law Basics

Prohibition, tied-houses, and the 21st Amendment

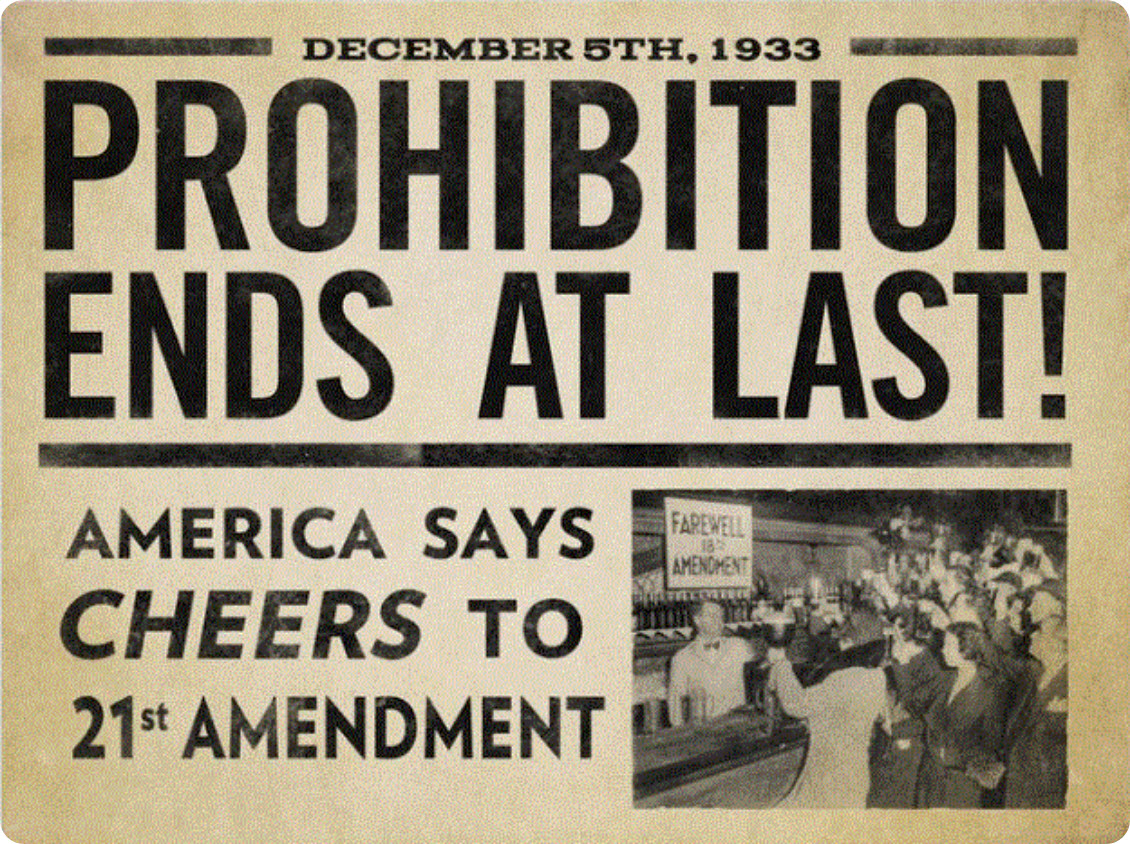

A variety of factors led the U.S. to adopt the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, which led to Prohibition in 1920, banning the manufacture, sale and transport of alcoholic beverages in the U.S. Central among those factors were the “tied-house evils,” which many believed led to intemperance and other societal issues that warranted Prohibition.

“Tied-house” refers to the practice of tying a supplier’s products to a specific bar or other type of retailer. For example, one supplier’s “house” would serve only that supplier’s brands of beer, while other suppliers secured their own “houses” that sold only their brands of beer. This arrangement was a common practice in the U.S. before Prohibition and still is common in England and other parts of the world today. In the U.S., tied houses were thought to lead to a variety of social problems, including intemperance, as bars competed for business and dropped prices, sometimes to below cost. One common practice was for bars to offer a “free lunch” with the purchase of a beverage to attract customers. They’d then recover their costs by aggressively promoting alcohol and encouraging overconsumption, typically by offering a lunch that was high in salt. This practice was the genesis for the expression, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

Prohibition ended in 1933 with the adoption of the Twenty-first Amendment to the Constitution. The Twenty-first Amendment left the primary regulation of alcohol to the discretion of the individual states, and the end of Prohibition thus brought with it the immediate need on the part of each state to pass laws that sought to avoid the issues that led to Prohibition in the first place. The resulting laws are often referred to as “tied-house laws.”

The three-tier system

The three-tier system generally requires manufacturers (aka suppliers) to sell their products to wholesalers, who in turn sell the products to retailers, such as grocery stores, convenience stores, liquor stores, bars, and restaurants. As a general matter, the three-tier system functions to prevent manufacturers from selling their products directly to retailers, thus arguably preventing tied houses. The Alliance members work within each state’s three-tier system by delivering alcohol to consumers from the same licensed retailers that sell alcohol to consumers in the tradition brick and mortar environment.

Central to each state’s three-tier system and associated tied-house laws, cross-ownership between the tiers is generally prohibited, in order to prevent vertical integration and insulate retailers from the influence of manufacturers. In addition to establishing separate licenses for each tier and prohibiting entities and individuals from holding licenses in more than one tier, state legislatures adopted a variety of other laws to ensure adequate separation of the industry members in different tiers.

Following the repeal of Prohibition, and in the nearly 100 years since Prohibition ended, a complicated patchwork of state laws has arisen, in some cases to further the three-tier concept and in other cases providing exceptions to these general principles.

What are control states and what are license states?

As states exercised their discretion to enact alcohol laws after Prohibition, some states opted for the state itself to play an active role in the sale of alcoholic beverages. These “control states” have state monopoly over the wholesaling or retailing of some or all categories of alcoholic beverages. The rest of the states opted to allow the private industry to handle the sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages, but continued to maintain oversight and control through licensing and taxation. These are referred to as “license states.” Some states have a mix of license and control systems. For example, a state may control retail sales of distilled spirits through state-run liquor stores, but allow private businesses to sell beer and wine upon issuance of a license. Likewise, a state may have control over the wholesale distribution of alcohol – deciding what products are available for in-state licensed retailers to purchase.

The current states that control some aspect of the wholesale or retail of alcoholic beverages include Alabama, Idaho, Iowa, Main, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, Wyoming, and Montgomery County, Maryland.

Licensure and jurisdiction

Each state’s licensing regime gives alcohol regulatory agencies the tools to define how different license holders can operate, and gives the agency jurisdiction to enforce against license holders for noncompliance. When license holders exceed their license privileges or otherwise operate outside the bounds of the state’s alcoholic beverage laws and regulations, the state’s alcohol regulatory agency can enforce against the license holder, typically with a variety of penalty options, ranging from fines to license suspensions, to license revocation, depending on the nature of the violation. The Alliance members each operate within each state’s licensure system and their associated privileges by delivering for licensed alcohol retailers that hold the privilege to deliver alcohol to consumers using a third party.